Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg made waves earlier this month for his appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast, in which he discussed his decision to end diversity, equity and inclusion efforts at Meta and lamented a perceived dearth of masculine energy in the corporate sector. “I think a lot of the corporate world is pretty culturally neutered,” Zuckerberg observed. “Masculine energy is good, and obviously, society has plenty of that, but I think corporate culture was really trying to get away from it.” Veteran politico James Carville had similarly choice remarks to make about women’s influence in the Democratic Party and the extent to which they contributed to Harris’s defeat. In a NYT interview with Maureen Dowd late last year, Carville theorized that there are “too many preachy females [in the Democratic Party]… ‘Don’t drink beer, don’t watch football, don’t eat hamburgers, this is not good for you’... The message is too feminine: ‘Everything you’re doing is destroying the planet. You’ve got to eat your peas.'”

These remarks stem from a common underlying idea: women’s influence, women’s power, has somehow gone too far, to the detriment of men and masculinity, and at the expense of our success as a collective, whether that’s a company, a culture, or a political party. Trump’s first term helped catapult #MeToo into the spotlight and brought women’s experiences of discrimination, harassment, and violence into the mainstream conversation, but the subsequent four years sent the pendulum swinging back. Grievance abounded. #MeToo went too far, the movement victimizes men, elevates women’s vendettas over men’s right to the presumption of innocence, and generally contributes to a culture of punishing men for existing and demanding that they stay quiet. Men are turning rightward because they’re marginalized by the left. Childless cat ladies are destroying America! How widespread is this notion that:

(1) women have advanced

(2) at men’s expense?

Gender Discrimination Is Zero Sum, Too

I decided to replicate a study I shared in a prior piece that demonstrates white Americans are prone to zero-sum perceptions of racial progress, but I applied it to gender attitudes. A month before the election, I asked voters to rate the average level of discrimination they think men and women have faced in each decade from the 1950s through the 2020s. Here’s what I found.

True to my expectation, much as white people perceive racial progress is a zero-sum game that Black Americans are winning, men perceive gender discrimination as a zero-sum game that they are now losing. Not only do they perceive that anti-men discrimination is on the rise and anti-women discrimination is in decline, they believe there is currently more anti-men discrimination than anti-women discrimination in society writ large. Women, on average, also perceive the same decline in anti-women discrimination and corresponding rise in anti-men discrimination since the 1950s, but they do not think that men have it worse, in absolute terms, than they do themselves.

I’m guessing your next question is: which men? I will answer that, but I want to plant a second question: which women?

It’s not Democrats. Democratic men (and women) perceive a very mild increase in anti-men discrimination since the 1950s, and a modest decrease in anti-women discrimination, but neither perceive that men now have it worse than women as a consequence of these shifts.

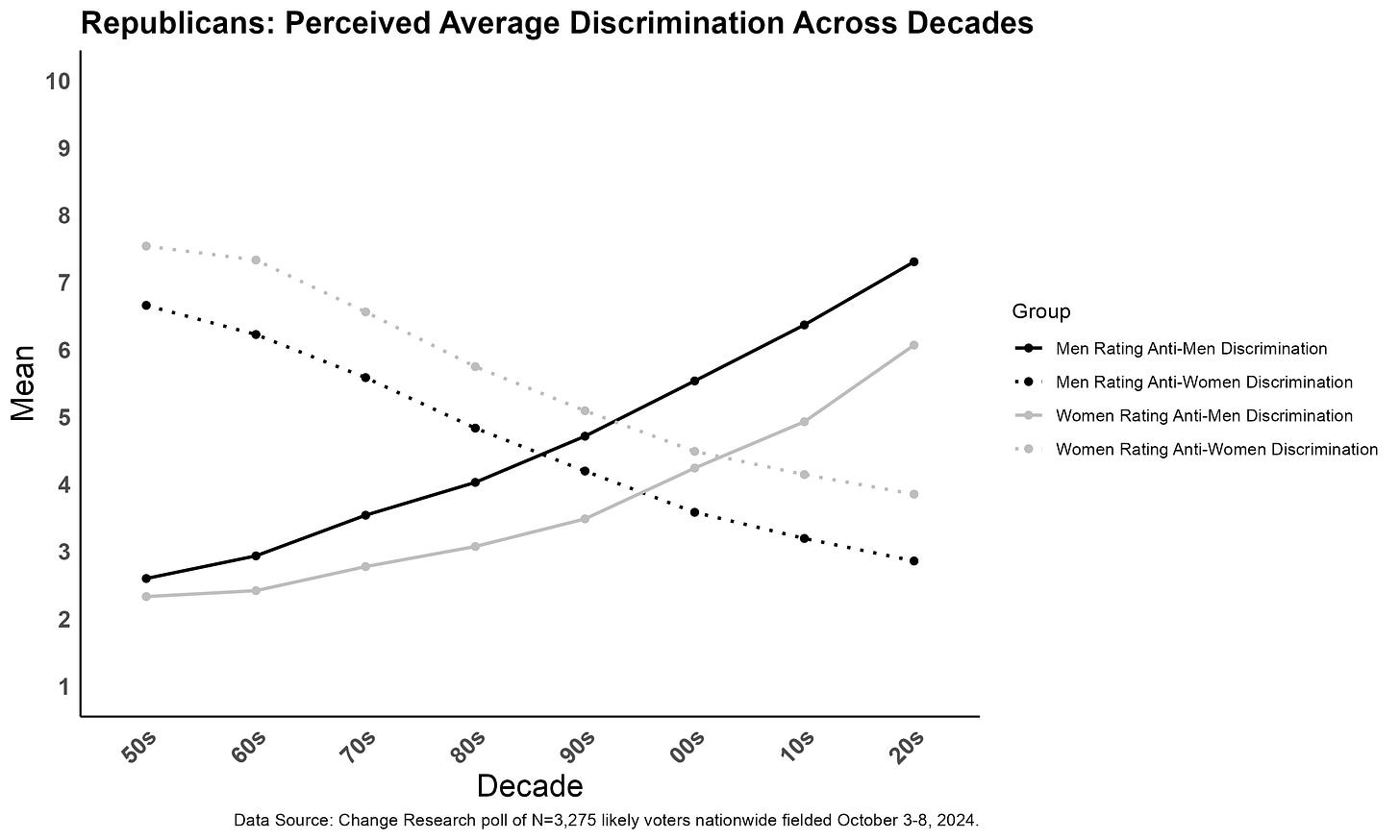

Now, for the Republicans.

There are a few noteworthy findings in this data. First and foremost, it’s Republican men and women that are driving this trend. Both perceive anti-women discrimination is plummeting and anti-men discrimination is soaring, and both perceive men have it worse than women—by a long shot—when it comes to discrimination these days.

The second noteworthy finding is that men and women seem to place these shifts in different decades. Republican men, on average, place the inflection point in the 1990s; Republican women place it in the 2010s. I think it’s noteworthy that both of these decades brought very high-profile Supreme Court nominations in which the nominee, both times a man chosen by a Republican president, was accused of sexual misconduct on the national stage. I don’t claim that either of these events are the only, or even the primary, reasons for this pattern of data, but I do suspect they were critical moments in the national conversation that may have produced sustained attitude change. Consider that support for Kavanaugh among Republican women rose from 49% to 69% after he and Christine Blasey Ford testified publicly before Congress in 2018.

The third thing to note about this data is that Republican men perceive anti-men discrimination to be exceptionally high, averaging around an 8 on a 1-10 scale. Let me put that into sharper context. The degree of discrimination that Republican men believe they are experiencing today is roughly equal to the amount of discrimination that white people believe Black Americans experienced in the 1960s.

Aside from the disturbing and obvious, one thing I want readers to take away from this data is that gender does not transcend partisanship when it comes to politics. Simply being a woman does not produce gender solidarity when partisanship is a source of cross-pressure.

The other, less obvious takeaway I want to impart is that all is not lost, because voters contradict themselves. Republican women, on average, view discrimination against men as more prevalent than discrimination against women, but per a Change Research poll conducted only six months earlier, 40% say that in American society today, women are valued less than men. 30% also believe abortion should be legal in most or all cases.

I’d argue this is more evidence for my overarching argument that pivoting away from hard topics because we sense a cultural headwind is rarely, if ever, the right approach. Most voters are not ideologically consistent because most don’t really subscribe to governing political ideologies; being a partisan and being an ideologue are not the same thing, and while the former is common, the latter is rare.

I won’t presume to tell anyone that this reality isn’t sometimes frustrating, or that the state of public opinion when it comes to gender discrimination isn’t extremely grim. Nor do I want to sanewash the broader threats to egalitarianism and democracy that Trump and Trumpism pose by saying “buck up and poll/message your way through it, this is business as usual.” But I’d argue strongly that this data I’ve shared doesn’t have to be cause for despair, either. In this era of polarization, virtually everything is won or lost on the margins. That means we can, and should, see voters’ ideological inconsistencies as opportunities.